The battles and atrocities of the Second World War were once waged across the Earth, claiming the lives of millions. Today, our remembrance of the War honors those souls and prevents the repetition of events that once threw the world into immeasurable darkness. We remember the millions who fought and died for liberation, the millions who perished under evil tyranny, and millions more who were simply caught in the web of devastation. Naturally, each nation of the world shines its own proverbial spotlight of remembrance, recounting mostly the stories of its own people braving battle and untold hardship, while understandably forgetting the stories of others. Of course, ones own remembrance does not diminish the respect payed to other peoples of the world, especially the honor earned by peoples in their fight for the liberation of others. Among the theaters of World War Two, Europe commonly claims the largest collective spotlight of remembrance, for it is the continent of the both the Eastern and Western Fronts, the Holocaust, and the spawning of evil that perpetrated unprecedented human suffering. However, one great nation’s story of the Second World War, often forgotten by many in Europe, unfolds on the other side of the world amid the vast and endless ocean of the Pacific. While Americans fought on the Western Front of Europe, they also fought another war, one which was far more personal and savage. Today, we remember the American story of the Pacific Theater, ingrained into the history of the United States. As our attention shifts across the continents and over the Pacific Ocean, we embark on a journey of remembrance, focusing on a seemingly insignificant island: Iwo Jima.

An essential part of our remembrance manifests in the form of footage and photographs, which remain our only glimpse into a fading past. One day, when all the people who once fought and survived the Second World War inevitably leave this finite world, their stories will represent the final breath of life that animates these distant images. Pop culture also serves our remembrance, bringing the stories of World War Two to wider audiences via a consumer friendly format, yet such retelling would never achieve authenticity without the images and stories.

When one thinks of the Second World War, a few iconic images may come to mind. One of those images, forever etched in American history, was captured from the battle of Iwo Jima 80 years ago, and it lives as a cornerstone of American commemoration.

This is it.

It is titled: Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima.

In American history, this is perhaps the single most iconic image of World War Two.

But what is its story?

This is what we will discover, learning about this image within the context of the Pacific Theater and its grim reality, told through the surviving images that honor the fallen.

Iwo Jima is a small volcanic island part of the Ogasawara Archipelago, south of Japan. In 1945, continuing a grueling island hopping campaign that had already encompassed most of the Pacific, the Americans set their sights on Iwo Jima, the first of Japanese territory they would face.

The occupation of Iwo Jima was critical for the remainder of the Pacific campaign. Securing the island would eliminate a Japanese airfield from which the Americans were under constant harassment, provide American fighters and bombers with a new airfield closer to Okinawa and the Japanese home islands, and aid significantly in the anticipated invasion of the Japanese mainland, granting American aircraft another safe place to ditch after conducting long range operations.

As the Pacific war neared its end, the Japanese grew increasingly desperate, resorting to heightened measures of fanaticism and inhuman savagery, fueled by indoctrination and delusion. Additionally, this battle with the Americans was to be different than all those previous, for this island belonged to Japan and its Emperor.

With undying devotion to the Emperor, compelled by their State Shinto religion and a cultish perception of self-honor, the Japanese garrison of around 20,000 soldiers was mandated to defend Iwo Jima to the last man.

The cost of Iwo Jima would catch American Marines by surprise, as they braved an unprecedented defense meticulously designed to kill at every hill and corner.

Beginning on February 16, 1945, the entirety of Iwo Jima was bombarded during daylight for three days continuously. American battleships, lined up off the island’s east coast, fired their deafening guns for periods of six hours, pausing with a break before continuing again.

Each naval vessel with heavy armament, especially those bearing 380mm cannons, was assigned its own sector of Iwo Jima to decimate, then the island was enveloped in a storm of hellfire by the warship symphony.

It is unknown how many Japanese defenders fell to the bombardment’s unending destruction, but its effect was surely piercing with terror, as Japanese soldiers took refuge in crumbling tunnel systems expecting the death token of every following shell to collapse the earth above.

On February 17, the ships fired shells of white phosphorous smoke to conceal the approach of a small operation. An Underwater Demolition Team (UDT-15), predecessor to the U.S. Navy Seals, was deployed in an attempt to conduct reconnaissance on Iwo Jima, inconspicuously landing at the Blue beach sector. However, the American divers were soon spotted by Japanese soldiers and fired upon, escaping with the death of one diver.

American intelligence on Iwo Jima’s defenses lacked severely, but the invasion plan was given an optimistic green light nevertheless. Once the invasion was set in motion, nothing more could have been done to prepare the Marines for what awaited them.

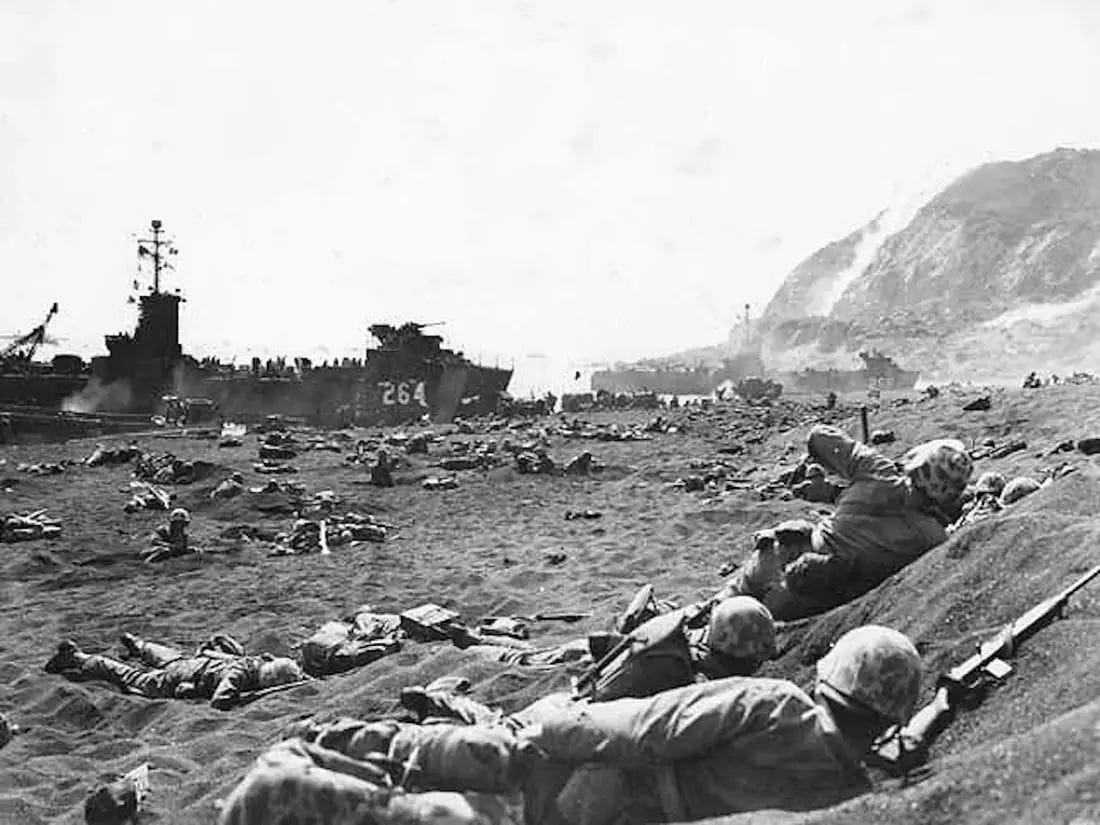

The aftermath of the bombardment saw the island riddled with thousands of craters, as the U.S. amphibious invasion, named Operation Detachment, commenced during the warships’ final salvos.

Marines loaded into the LVTs and deployed.

One who has never seen war cannot possibly know what thoughts dwelled in the mind of every man on those LVTs, bobbing and creeping slowly towards a Pacific no man’s land with an eerie suspense.

In a cute attempt to place ourselves in such an unimaginable situation, we may compare this experience to the beginning incline of a rollercoaster, as the ascent fuels a fire of anticipation and anxiety within, before cresting the track into the dive. Only now, multiply this feeling to the degree of unbearable, within our mind of limited comprehension, knowing certainly that the crest may guarantee a horrific departure from this finite world.

This is what those Marines probably felt.

At 0859 hours on February 19, 1945, the first wave of Marines landed on Iwo Jima’s volcanic sand beaches, encountering no resistance.

The island was silent.

The Marines began to believe that the bombardment might have actually eradicated the defenders, or perhaps sent them cowering. Meanwhile, as the landing sites became congested with more waves of Marines and tanks, the first wave struggled with advancing up the steep sandy slopes of the beach, rendering the Marines a condensed and increasingly juicy target.

Unknown to the Marines, the burrowed and undeterred Japanese were patiently observing their landing from all possible vantage points, from the caves of Mount Suribachi down to the brush covered pillboxes just further up the beach, holding their fire.

The Japanese commander of the island’s garrison, Lieutenant General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, waited for the beach to fill with Marines. This was according to his defense plan. Throughout the course of the Pacific War, the crippling destruction of the Japanese fleet, numerous defeats at the hands of the Americans, and unavailability of reinforcements for Iwo Jima, led Kuribayashi to one conclusion: He could not win.

Thus, the resistance of Iwo Jima was aimed only at exacting the greatest cost possible for the Americans, and every Japanese was expected to die honorably for it.

Around 1000 hours, Kuribayashi gave the order to open fire, and all hell was let loose.

Robert Leckie, a Marine veteran of the Pacific War, best depicts the unfolding situation in his book, The Battle for Iwo Jima:

“At first it came as a ragged rattle of machine-gun bullets, growing gradually louder and fiercer until at last all the pent-up fury of a hundred hurricanes seemed to be breaking upon the heads of the Americans. Shells screeched and crashed, every hummock spat automatic fire and the very soil underfoot erupted with hundreds of exploding land mines. In everyone's ears was the song of unseen steel: the shriek of shells, the sigh of bullets, the sobbing of the big projectiles and the whizzing of shrapnel. Marines walking erect crumpled and fell. Concussion lifted them and slammed them down, or tore them apart — sometimes hurling a man's arms or legs thirty or forty feet away from his body” (1967).

The Marines received machine gun, artillery, and mortar fire from almost all angles, especially from caves of the fortified Mount Suribachi to their south.

Witnessing the death and violent mangling of their comrades, some surviving Marines were somehow able to reach the southern tip of Airfield No. 1, indicated on the landing plan map, by the end of the first day.

On February 19, the landing at the beaches and subsequent combat left one landing group, the 25th Marines' 3rd Battalion, with only 150 fighting men out of the original 900—they suffered a catastrophic 83% casualty rate.

American commanders did not expect this.

However, on day one, the 28th Marines had cut across the narrowest width of Iwo Jima from Green Beach, isolating Mount Suribachi.

Additionally, around 30,000 additional Marines had landed on the secure beachhead that day.

The battle was only beginning.

On February 23, the 28th marines began to scale Mount Suribachi, remarkably finding no resistance as the Japanese hid in tunnels beneath their feet.

That same day at 1030 hours, they summited the mountain and raised the American flag.

But it was not the flag most think of.

Unknown to many, this was the first flag raised on Mount Suribachi. It is the original that was forgotten to mainstream history, the first mark of victory, honoring the lives given to plant that flag.

Upon the sight of the first flag, the Marines below Suribachi elated with cheer, and the ships on the beach blasted their horns.

Later that day, it was decided that the flag was too small to be seen at farther distances, so a new party of Marines retrieved a larger flag from the ships below and scaled the mountain again.

It was then that Joe Rosenthal, a photographer with the Associated Press, joined the party up the mountain and captured the second flag raising, almost missing the iconic moment while he took his position to photograph.

In America, the image became sensational.

After Iwo Jima was declared a victory, the second flag raising was published on magazine covers, printed on posters, and even used as the 1945 U.S. postal stamp. Rosenthal would win the Pulitzer Prize for Photography in 1945 for his legendary capture of American determination.

However, despite the capture of Suribachi and the flag raising, the battle for Iwo Jima was still far from over, as the Japanese remained further north.

Tragically, three of the six men pictured in the second flag raising would be killed in action during the following weeks, among thousands more.

Lieutenant General Kuribayashi’s main stronghold controlled the northwestern portion of Iwo Jima.

Within the fierce fighting to capture Iwo Jima’s airfields and eliminate the stronghold, Marines were cut down by deplorable but admittedly cunning tactics of the Japanese.

An intricate tunnel system ran through the entire island, some tunnels of which remain possibly undiscovered to this day. Utilizing this advantage, the Japanese would often appear behind the Marines’ front line, emerging from discreet entrances previously undiscovered and killing many of those unaware.

Some Japanese who spoke English would pretend to be wounded Marines, calling for American medics from an unseen location, promptly shooting them as they approached to help.

Amid the mounting casualties, the Marines utilized their own tactics to deal with the Japanese. In additional to small arms, personal flamethrowers, flamethrower tanks, and satchels filled with a massive yields of TNT dispatched of the defenders in their tunnels quite effectively, although horrifically.

On the 21st of March, Kuribayashi’s stronghold was captured and destroyed with explosives. The following days saw mass suicidal banzai charges of up to hundreds of Japanese at times, who were almost all massacred in a hail of bullets while inflicting dozens of casualties on the Marines. Tadamichi Kuribayashi was never found, nor identified among the dead. It is unknown how the Japanese commander perished.

80 years ago today, on March 26, 1945, the island was declared officially secure, and the Battle of Iwo Jima was over.

Even after this declaration, over a thousand Japanese holdouts continued to resist on Iwo Jima, and although mostly eliminated, some individuals would evade capture and not surrender until 1949, an astounding four years after the end of World War Two.

Iwo Jima was the only Pacific War battle where total American casualties exceeded those of the Japanese. Over 26,000 American casualties payed the price of Iwo Jima, including 6,821 killed. The Japanese garrison fulfilled its goal of a high cost, while nearly all perishing. Most Japanese fought to the death, resulting in around 18,000 Japanese either killed or missing in action, with only around 200 captured during the battle.

Today, debates persist on whether seizing Iwo Jima was necessary for the American campaign and the cost of life. Despite this, the people who gave their lives for their country, and the world, still deserve to be honored with respect.

Their honor is immortalized in that iconic image.

They are honored on the summit of Mount Suribachi today, as Americans and Japanese gather on Iwo Jima to commemorate the fallen, some remembering comrades, and others, ancestors.

The fallen are even honored by us, as we learn about the events they endured, their valor, and their untold sacrifice in the name of goodwill.

Every image holds a story. This is the story of Iwo Jima.

Iwo Jima is only the first Pacific battle we commemorate in this series. 80 years ago, as April approaches and the War in Europe draws to a close, the allies in the Pacific face more to come.

Next, we sail to Okinawa.

It will be the final major battle of the Second World War.