It remains a battle often forgotten in time, having brought carnage upon a historical city that managed to survive most of the Second World War unscathed. It is a story of evil resistance annihilated by an onslaught of proclaimed “liberators”, with a populace suffering under brutality. Like many battles before, it was a human meat-grinder. Room-to-room combat claimed countless lives, as thundering artillery rang perpetually throughout the husk of a once beautiful city. It all started eighty years ago today—the snuffing of one of the Reich’s final flames. This was the siege of Breslau.

Wrocław, the historical capital of the Silesian region, thrives today as a quaint Polish city with humble attractions worthy of appreciation. Perhaps the Wrocław Zoo claims the spotlight for the city’s most well-known attraction; it is the largest zoo in Poland, taking the title as the third most extensive zoological garden in the world. Rewinding time by eighty years, however, this city was known for a far less pleasant environment. It was the city of Breslau, a German city that would soon find itself within a miserable setting, ravaged and teeming with death.

On February 16th, 1945, the Red Army began its siege of this cultural city during the final months of the Second World War, poised to destroy another holdout of Hitler’s dwindling Nazi fanatics.

German Preparations

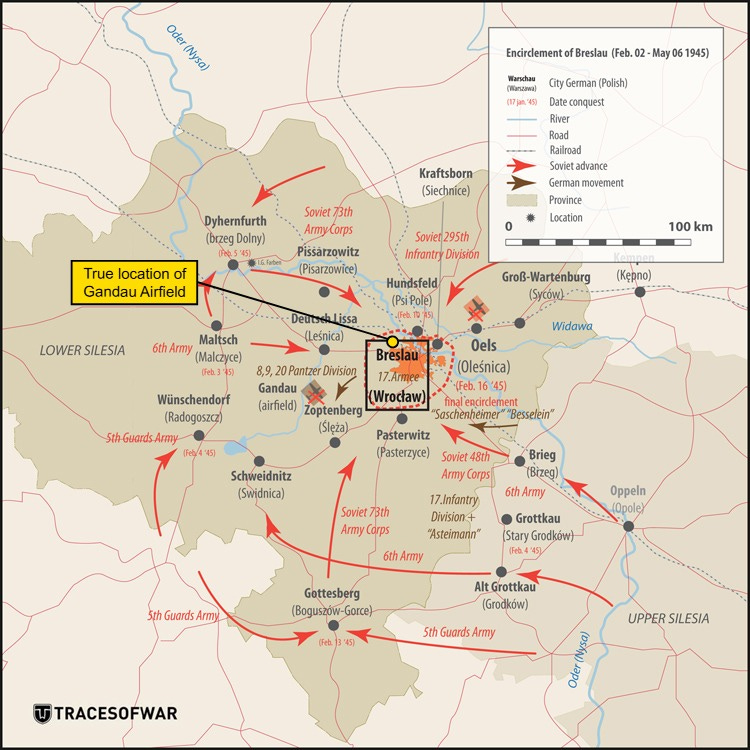

The Soviet encirclement of Breslau, achieved on February 16th, was the objective of a series of Red Army advances beginning the weeks prior, part of the Lower Silesian Offensive officially launched on the 8th of February. This new offensive rode on previous successes of the Vistula-Oder Offensive, aimed at securing southern roads that would aid continuous supply to the frontline creeping on Berlin. Breslau stood at the strategic junction for these roads, and it soon found itself under hellfire.

In August, 1944, Hitler himself declared Breslau a Festung (fortress holdout), the same status that the city of Poznań would receive in January 1945, as we covered previously. Immediately following the declaration, the construction of fortifications began, utilizing the unique advantages of the city, as Breslau was surrounded by many natural barricades against enemy armor, such as marsh wetlands. The Germans barricaded streets with tank traps and other obstacles, fortified buildings and squares, and leveled entire buildings on the corners of intersections to provide increased firing angles. Out of town, they dug trench networks, placed minefields and installed machine gun nests to watch dreadfully over them.

Initially, Breslau’s Kampfkommandant, Karl Hanke, forced the local population to complete the arduous work. Later, POWs and other forced laborers completed the fortifications. Hanke was a Nazi fanatic personally appointed by Hitler as Breslau’s “battle commander”, and during his governance he gained the despicable nickname of “Hangman of Breslau”, for the execution of over one thousand people on his orders. Near the end of war, Hanke would not escape his seemingly karmic fate.

By February, Festung Breslau was prepared for the impending Soviet advance, mustering a force of around 50,000 defending soldiers which included 15,000 Volkssturm (home guard militia). On paper, the Volkssturm seemed to bolster the German military quite substantially. However, the fighting value of these combatants was equivalent to cannon fodder. Volkssturm units were ill-trained and equipped, comprised of men previously exempt from military service, with ages ranging from as high as 60 to as low as 12 years old. Young children were incorporated into the Volkssturm via their membership in the Hitler Youth, which mobilized children in frontline combat as the war neared its end. These unfortunate children, poisoned by fascist ideals, were sometimes the first to repel the Soviet assaults in Breslau, as well as the first to die. The same case was especially present in Berlin.

The Battle Begins

After the combined force of the Soviet 5th Guards Army and 6th Army secured a wide encirclement of Breslau on February 16th, the Festungskommandant serving under Hanke, Generalmajor Hans von Ahlfen, was contacted by the Red Army and offered 24 hours to surrender.

He did not reply.

Soviet Siege (February - March)

The day following Ahlfen’s silence, Lieutenant General Vladimir Gluzdovsky ordered elements of his 6th Army to begin an assault into the city. On February 18th, the 218th Rifle Division attacked German defenders from the south, capturing a critical railway. However, on February 20th, the 218th was compelled to partially retreat after met with a counterattack by the 55th Volkssturm Battalion, made up of Hitler Youth children. According to journalist Richard Hargreaves, this attack was exaggerated in a German propaganda newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter, heinously glorying the child soldiers’ actions.

During these first days, strong German resistance stifled the initial probing assault, and Gluzdovky paused the siege. As the Soviets had fought into the city, the enemy grew in density among an urban environment. These circumstances mandated a more focused approach.

Meanwhile, a coordinated plan of attack was being drawn by the 6th Army headquarters.

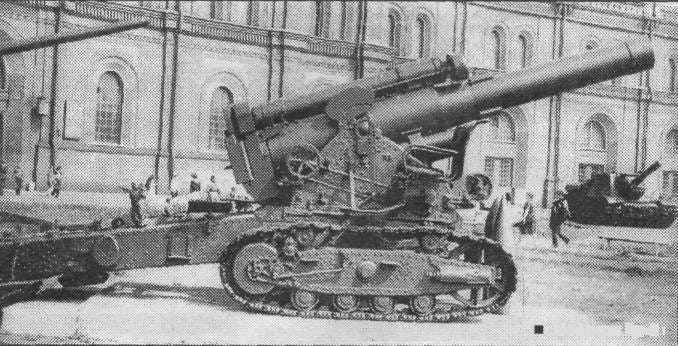

Deafening artillery fire rang out south of the city on February 22nd, at 0800 hours. The Br-5 280mm mortars fired upon Breslau for nearly three hours continuously, annihilating buildings and barricades, as any flesh caught in their devastation was pulverized. Between the 22nd and 23rd of February, the mortars fired over 100 shells, according to military historian Alexei Isaev. Not only did this bombardment soften the German positions, but it also served to erode their resolve with terror. The plan sprang into action.

Regrouped elements of the 6th Army launched their offensive into Breslau immediately following the barrage, closing on the city from all directions, with a main attack approaching from the south.

Each Soviet regiment deployed one assault battalion specialized in urban combat, totaling ten of such battalions. This was part of the new strategy. Hundreds of men comprised each assault battalion, including sapper groups, a flamethrower group, and a battery of 76mm anti-tank guns, supported by heavy weaponry such as the ISU-152 self-propelled gun (SPG). The SPGs and other artillery fired directly at fortified positions while protected by infantry, obliterating entire buildings from close range and crushing the German defenders beneath heavy rubble. Sappers with demolitions would prove especially useful in this purpose as well.

The fight was savage. Every room in every building had to be cleared, and as expected, the cost of life was high.

Not only did soldiers meet a grim end in the ensuing chaos—civilians did as well. Around 230,000 civilians remained in the city during the siege, caught under artillery and crossfire.

Anticipating the capture of Gandau Airfield in the west, which enabled the airlift of Festung Breslau since the Soviet encirclement, Festungskommandant von Ahlfen ordered the construction of a makeshift airfield in the east on February 23rd. The garrison demolished an entire district in attempt to fulfill this project, located today at Plac Grunwaldzki, and thousands of civilians and POWs were forced to complete the daring construction. As the siege went on, Soviet artillery killed many of them, and the airfield would never even be used.

In the south, the 6th Army advanced steadily, braving a horrific urban environment. German defenders fired on them from every angle. Shots came from high buildings, as well as from basement windows. The Germans were entrenched in underground tunnels, even flanking the Soviets through Breslau’s sewer system. When tanks crept down the street, the defenders emerged with Panzerfausten, firing shaped charges that penetrated their armor, killing crewmembers inside. An especially dirty trick by the Germans was the pre-rigging of buildings with explosives. As the communists captured each building, the Germans often attempted to retake them, and when they could not achieve this, the buildings were blown up along with their occupying soldiers, burying everyone.

By February 27th, the 6th Army reached the Hindenburg Platz, known today as Plac Powstańców Śląskich. Soon after, on March 1st, the Germans initiated a counterattack attempting a breakout from the encirclement, which failed.

As fighting continued, Generalmajor von Ahlfen was replaced by General der Infanterie Hermann Niehoff as Festungskommandant on March 8th, still serving under Kampfkommandant Karl Hanke. During March, German resistance grew in fanaticism as their hopeless situation deteriorated further. At one point, the Soviets encountered 40 Germans garrisoned in the St. Karol Boromeusz church, using it as strongpoint with heavy machineguns. After repeated attempts to take the church failed, and the defenders refused to surrender, Soviet sappers detonated the church along with its entire garrison. In another instance, the unyielding Germans occupied a school building near Hindenburg Platz, which the Soviets took after finally storming it with flamethrowers.

Around mid-March, the Germans launched another counterattack, this time in the Mochbern district south of Gandau Airfield, with the aid of an armored train. This effort failed as well, and by March 31st, the Soviets threatened Breslau’s lifeline of Gandau Airfield.

The Second Offensive and German Capitulation (April - May)

On April 1st, the 6th Army began a new offensive from the west after receiving reinforcements, preceded again by an artillery barrage. German forces desperately attempted to defend Gandau Airfield to no avail, as the Soviets eliminated them and captured the airfield within days. Their vital lifeline was lost.

With no other alternative of supply, the Luftwaffe dropped supplies by air during the night, and Soviet forces sometimes captured these goods. Moreover, the loss of the airfield prevented any further evacuation of wounded, adding to the German despair. On April 5th, Festungskommandant Niehoff’s report of the terrible situation eventually caught the attention of Hitler, who demanded the Festung be held to the last man.

By the end of April, Soviet forces had captured a portion of the northern city district, most of the southern district, and the entire western district. With this achievement, the 6th Army ended its offensive and held defensive positions, deeming any further attack unnecessary.

At any day, Berlin was expected to fall.

In the final days, artillery continued to bombard what remained of the German garrison, as Soviet propaganda blared on loudspeakers throughout the ruined city. Pamphlets were even dropped on Breslau by air, attempting to compel a surrender. Some defenders, intending to surrender, were caught by their SS commanders and summarily executed for cowardice.

Ironically, Berlin surrendered on May 2nd, and Festung Breslau still continued its futile fight even after learning the news of Hitler’s death.

On May 4th, clergymen of the Roman-Catholic churches approached Niehoff and urged him to end Breslau’s suffering and surrender, but Niehoff was still reluctant.

The Kampfkommandant, Karl Hanke, somehow fled from Breslau on May 5th and flew to Prague. Months later, while faking his identity as a common infantry man, he attempted to escape capture by catching a moving train. Czech partisans shot him before he succeeded, and his skull was smashed in with a rifle butt.

Also on May 5th, German communist commandos of the Nationalkomitee Freies Deutschland posed as a Wehrmacht kampfgruppe of stragglers, donning uniforms and bearing German small-arms. They successfully infiltrated the Breslau garrison and killed suspicious Nazis while trying to persuade others to surrender. However, they were soon discovered and their operation had failed.

The early morning of May 6th—Hermann Niehoff comes to his senses and issues a proclamation to his troops.

"Hitler is dead, Berlin has fallen... The last cartridge has been fired - we have fulfilled our duty" (Institute of National Remembrance).

He makes contact with the 6th Army and requests negotiations. At 18:20, the capitulation is signed.

It is over.

Aftermath

Today, the casualties are not officially known, and they may never be.

During the Siege of Breslau, as well as its prelude, it is estimated that between 20,000 and 170,000 civilians lost their lives.

The German garrison suffered around 6,000 dead, with 23,000 additional wounded. Meanwhile, estimates of Soviet deaths in Breslau range between 6,000 and 13,000, with total casualties possibly as high as 60,000, according to some sources.

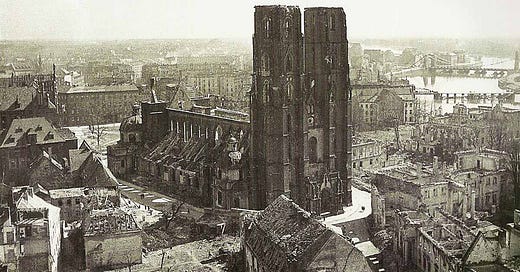

The city itself, once vibrant and rich, was a corpse of its former beauty. By May 6th around 72% of its buildings were destroyed or heavily damaged.

In the signed act of capitulation, General Gluzdovsky promised an honorable treatment of German POWs and civilians, including the preservation of personal safety and property.

These terms were never fulfilled.

Soviet soldiers pillaged the city, raped and sometimes murdered German women and young girls in evil acts of vengeance, wickedly justified by the previous suffering of Soviet peoples under German occupation.

This would serve as a reminder that the Soviets were never liberators, but instead, new conquerors, as they would continue to be for the next 44 years in Poland.

After the complete surrender of Nazi Germany and the end of the War in Europe on May 8th, Breslau was given back to Poland and renamed Wrocław, in accordance with the terms of the Potsdam Conference.

Today, as people live in peace, there are still scars of Wrocław’s past.

May such a past never come again.